AIDS: THE LOST VOICES

IN MAY 2024 we examined press coverage of Roger Youd, initially labelled by journalists as “the Monsall Patient,” a 29-year-old man detained in hospital under a recently enacted piece of legislation applied by the local authority; the measure, perhaps intended to protect vulnerable people, was widely criticised as poorly executed after Roger’s solicitor and barrister publicly stated there was no evidence his condition met the statutory criteria for such a detention order.

It was only after the episode aired in May 2024 that Roger’s brother Carlton stumbled across our initial message, hoping he might take part in that programme. Over time Carlton has been exceptionally helpful, sharing facts, correcting inaccuracies and giving a fuller insight into his brother Roger’s life. His candour drove home how Roger’s diagnosis and detention – widely reported in the national and international press – affected not only Roger but reverberated through the family, exposing the emotional, practical and reputational toll on those closest to him.

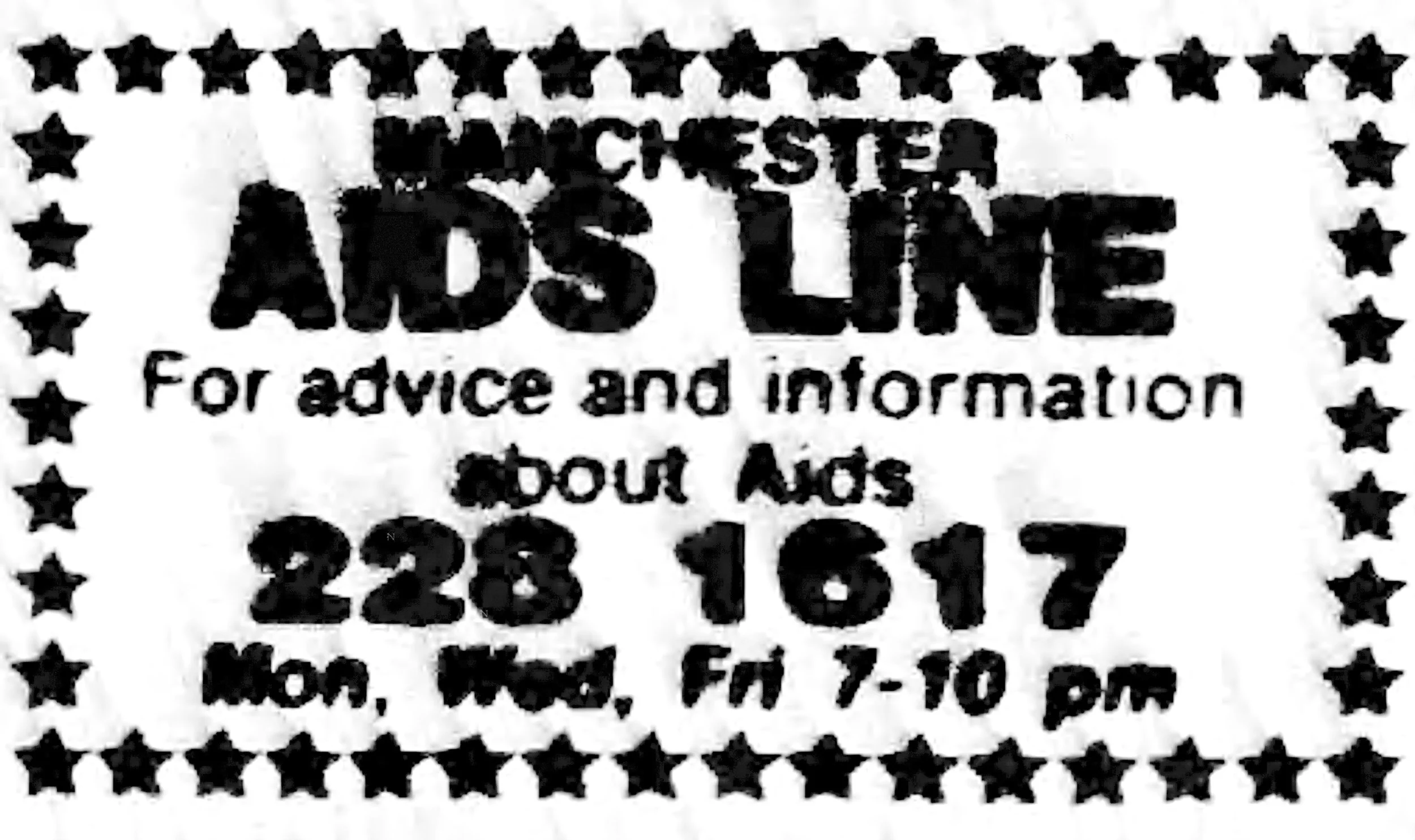

In the latest episode, "Remembering Roger Youd," published on the 40th anniversary of Roger’s untimely passing on 16 December, intimate recollections from his brother Carlton Youd sit alongside an inspiring interview with Paul Fairweather — a close friend and longstanding, respected LGBT and HIV/AIDS activist who helped establish Manchester’s AIDS line along with the picket and protest in response to Roger’s unlawful detainment.

We also hear first‑hand accounts of Roger’s deep friendship with Ian, a bond so close they mischievously called one another “sisters,” a small, wry testament to the humour that sustained them. Roger’s catalogue of imported disco records — traded for the use of Ian’s solarium — made for a friendship that endured through ordinary joys and the looming, unknowable crisis to come, AIDS. The episode stitches these personal memories into the wider fabric of Manchester’s gay community, juxtaposing tender recollection with the hard history of a city on the brink of the AIDS epidemic. In doing so it offers an unflinching, compassionate tribute to Roger: to the friendships that shaped him, and to the activist networks whose fight for his freedom and care helped redefine support for a whole generation living with HIV/AIDS.

Carlton Youd - Roger’s Brother…

It was a real privilege to speak with Roger’s brother Carlton, who offered clear, humane insight into Roger’s detainment, the toll it took on the Youd family and the quieter details of his brother’s life. Speaking with Carlton reminded me how strange it must feel for strangers to want to peer into what is usually private family life — yet his openness helped cut through the sensationalism that surrounded Roger’s unlawful detainment at Monsall Hospital in 1985.

The press sought to turn a legal and medical injustice into a lurid story that vilified Roger and his family, but Carlton’s recollections restored a sense of normality. Roger was an ordinary, highly educated man, living his life much like anyone else, and his AIDS diagnosis did not make him any less human. Carlton’s calm dignity and the family’s endurance underline how much was lost in the headlines, and how important it is to listen to those who lived the experience rather than those who exploited it.

But Roger’s detainment has left a lasting legacy: no other person with HIV/AIDS was subsequently detained, whether through changes in legislation or by replication of the same panic-driven misuse of the law that resulted in Roger’s unlawful detainment order. The case became a cautionary precedent, exposing how fear and misunderstanding can warp legal processes and prompting authorities and the medical community to guard against detention on the basis of stigma rather than evidence, reinforcing the principle that public health measures must be grounded in science, proportionality and respect for individual rights.

Thank you to Carlton and the Youd family for sharing such personal insight into the life of a courageous young man. This generosity of spirit not only preserves Roger’s legacy but also strengthens the bonds of the HIV/AIDS and medical community that remembers and learns together, and ensures no such action is ever repeated.

IAN

Roger’s close friend…

Ian reached out after stumbling across our initial podcast episode about Roger’s detainment at Monsall Hospital in 1985 and the way the press had covered it, keen to add his voice to a story that had been reduced to headlines. He explained that he and Roger had first met in as a ‘liaison’ that had failed — but, at Roger’s suggestion, they became firm friends.

The pair clicked instantly over a shared love of music and a delightfully zany sense of humour, often calling themselves “sisters”, it was a pairing that “…was the best friendship I’ve ever had with somebody” . Ian’s contribution as a close friend brings nuance and warmth to a narrative the media had flattened, revealing the quieter, truer rhythms of their friendship as two gay men in 1980s Manchester

Paul Fairweather MBE

Friend of Roger and LGBT/AIDS Activist

AIDS Line: Oct 1985

Paul has been instrumental in gay rights activism since 1974 and in HIV/AIDS activism from 1984, playing a crucial role in establishing Manchester’s AIDS Line and co-founding the George House Trust, which has grown into a leading HIV charity; his decades of commitment to campaigning, support services and public education were recognised when he was awarded an MBE by the King in 2023.

Knowing Roger Youd before his detainment, Roger contacted Paul confident that he would mobilise action to challenge his detainment at Monsall Hospital; Paul recounted organising the protest and picket outside Manchester Town Hall, where demonstrators carried banners and placards both opposing Roger’s detainment and asserting the rights and dignity of people living with AIDS at a time of fear, stigma and official neglect.

“ “It was a real contradiction that the Manchester council, that was probably one of the most progressive councils both on HIV and LGBT issues, was detaining someone for having HIV. I think they really hadn’t thought it through and I think it was a panic overaction by some of the consultants and then, the council went along with it really””

IN ORDER OF PODCAST EPISODE - CLICK TO ENLARGE (OPENS IN NEW WINDOW)

There was a sense of shock that Roger’s detainment had not been held in a private court, that the British press had been able to report the hearing on the same day; forty years on, with a raised eyebrow, it remains remarkable that his detainment made it into almost every newspaper from the East to the West Coast of the United States.

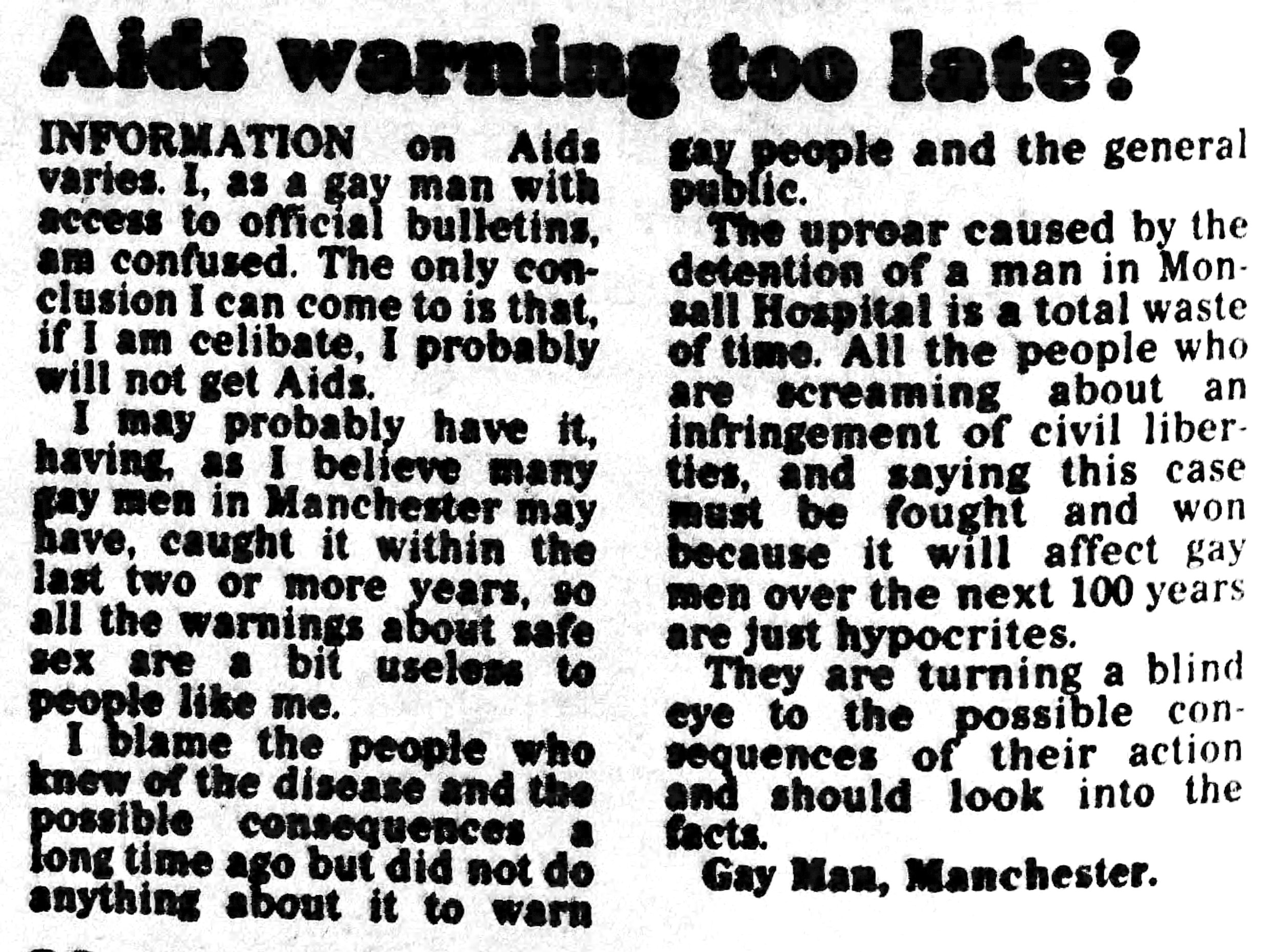

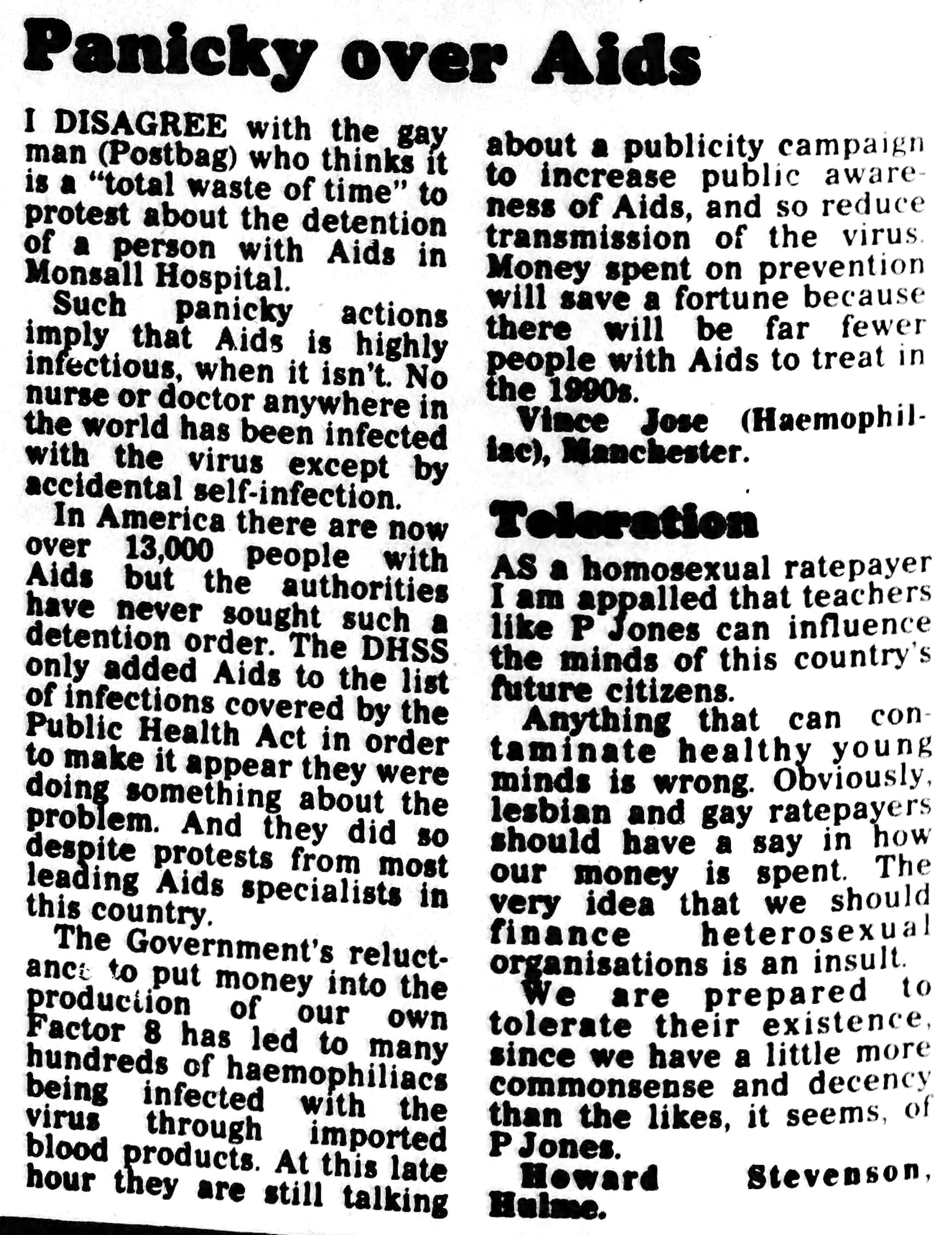

In October 1985, many weeks after Roger’s detention had been brought to an end by way of his successful appeal, two readers of the Manchester Evening News expressed sharply different opinions on the handling of the AIDS pandemic while referencing the action around Rogers detainment via the ‘postbag’ page.

Roger George Youd was born on 22 May 1956 in Flintshire, Wales, to Nellie (née Hughes) and Joshua Spencer Youd. One of four boys, he had an elder brother Graham and another elder brother, James Duncan, who was born in 1951 but sadly died in 1952 aged 14 months; Roger was followed by his younger brother Carlton in 1960. The family suffered further loss when the head of the house, the boy’s father, Joshua ‘Spencer’ Youd, died in 1974 when Roger was 18, and their mother, Nellie, passed away in 1998, thirteen years after Roger himself had died.

38 Detention in hospital of person with notifiable disease

Where a justice of the peace (acting, if he deems it necessary, ex parte) in and for the place in which a hospital for infectious diseases is situated is satisfied, on the application of any local authority, that an inmate of the hospital who is suffering from a notifiable disease would not on leaving the hospital be provided with lodging or accommodation in which proper precautions could be taken to prevent the spread of the disease by him, the justice may order him to be detained in the hospital.

An order made under subsection (1) above may direct detention for a period specified in the order, but any justice of the peace acting in and for the same place may extend a period so specified as often as it appears to him to be necessary to do so.

Any person who leaves a hospital contrary to an order made under this section for his detention there shall be liable on summary conviction to a fine not exceeding level 1 on the standard scale, and the court may order him to be taken back to the hospital.

An order under this section may be addressed—

(a) in the case of an order for a person's detention, to such officer of the hospital, and

(b) in the case of an order made under subsection (3) above,

to such officer of the local authority on whose application the order for detention was made, as the justice may think expedient, and that officer and any officer of the hospital may do all acts necessary for giving effect to the order.

Section 38 taken from the original Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984

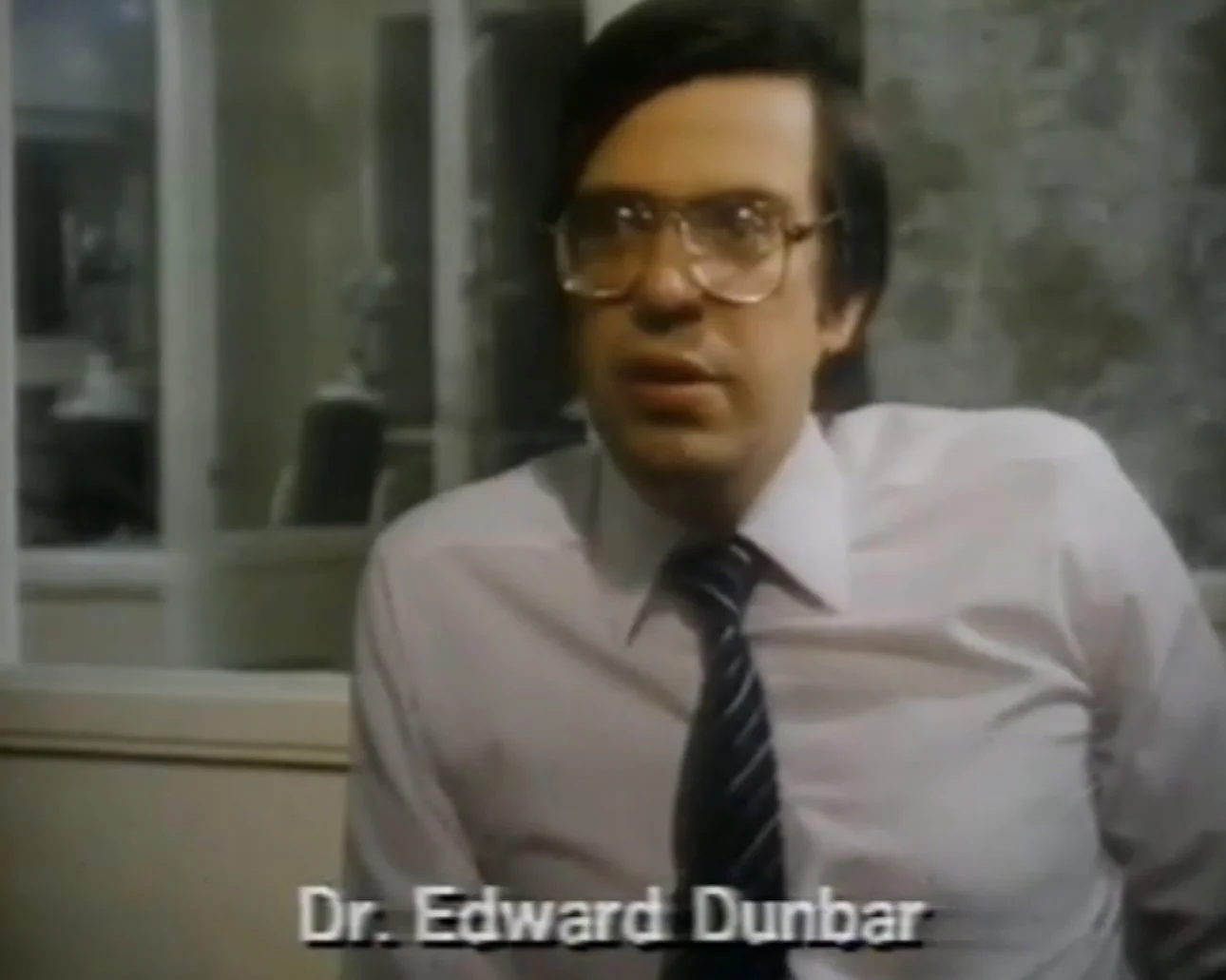

Roger’s detainment is briefly revisited in ITV’s TV Eye episode “AIDS and You,” broadcast on 7 November 1985, where archival footage and contemporary reporting in 1985 frame his case as emblematic of the era’s tension between public health measures and civil liberties.

At the time of recording (October 1985) and broadcast (7 November 1985), Roger remained a patient at Monsall, having chosen to stay there voluntarily after successfully appealing against his unlawful detention. The footage confronts his consultant, Dr Edward Dunbar, asking, “Looking back at the controversy that your actions stirred up, would you react any differently now if that same case arose?” — a question that presses at professional responsibility and the tension between clinical judgement and public scrutiny. I can’t help but wonder whether Dr Dunbar’s response would be different today, had he still been alive to answer it.

ROGER YOUD: Aired 7 Nov 1985, ITV [Thames TV/Freemantle]

On the 19 October 1985 the British Medical Journal published an article also questioning the validity of section 38 being applied in the case of Roger Youd.

The legal correspondent seems to have the same questions we had when trying to make sense of section 38 when HIV/AIDS was/is not a “notifiable disease”. You can read the one page article HERE.

Manchester News 14 Sep 1985

DR. ANNA ELIZABETH JONES, in 1985 was Manchester’s Cheif Medical Officer and the woman behind the application for the local authority to detain Roger Youd against his will.

It would have been interesting to ask her, perhaps quietly and directly, why she made the choices she did; given her standing as a highly experienced doctor of infectious diseases and her appointment as Manchester’s Chief Medical Officer, one would expect her clinical judgement and statutory responsibilities to align with established public health principles and legislation at the time.

We’d expect, as they did for solicitors, barristers and AIDS charities, that public bodies would repeatedly and unambiguously state that AIDS was not a “notifiable disease” and that the order obtained by Dr Anna Jones was unlawful; yet when activists and even the Manchester Evening News make the same point, it inevitably raises troubling questions about Dr Jones’s judgment and suitability for office.

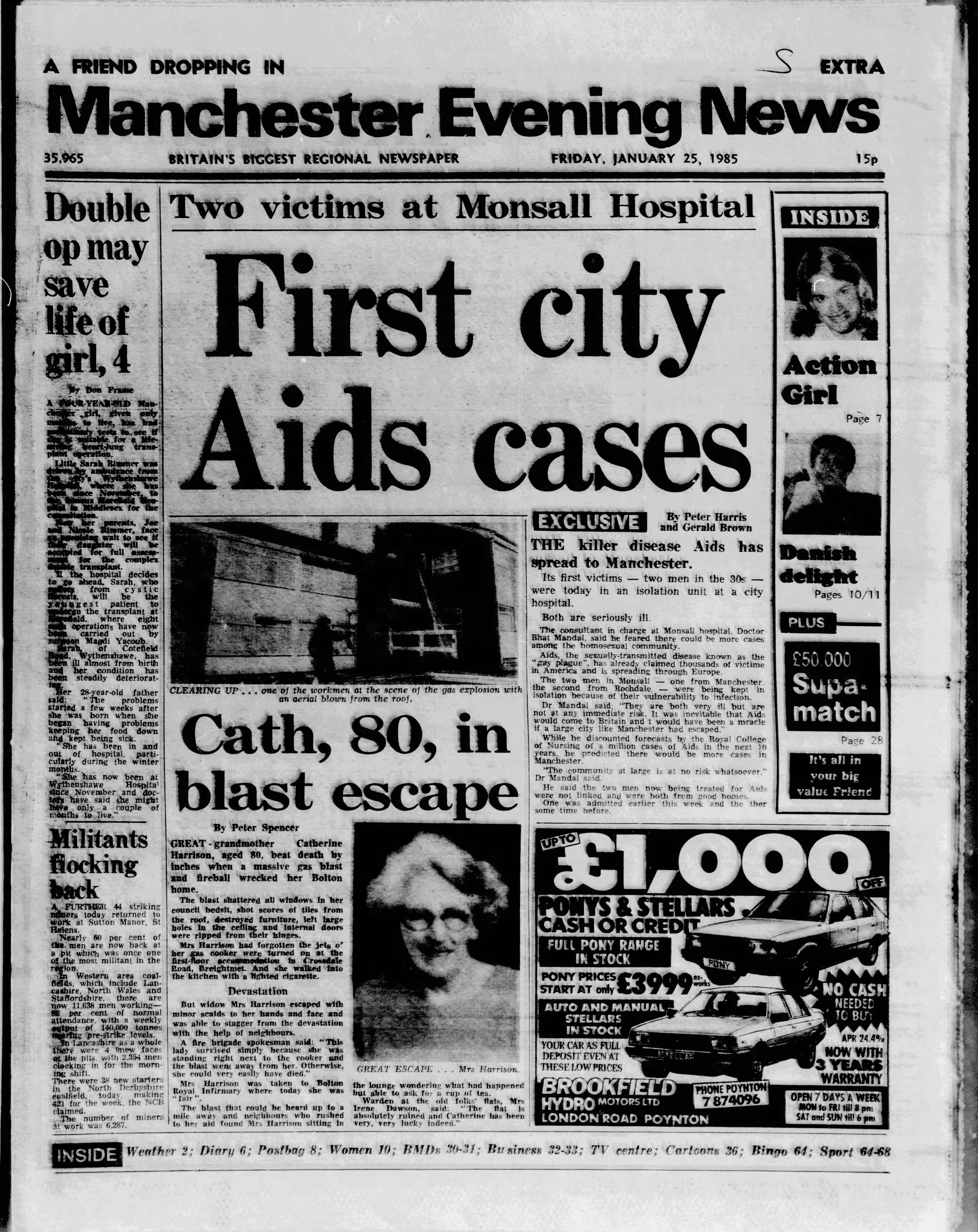

Silence or equivocation from official quarters looks less like prudent legal caution and more like a panicked overreaction, especially when viewed against earlier public statements: nine months before she sought the order on Roger Youd, she was quoted in the Manchester Evening News on 26 January 1985 discussing a story of two AIDS patients in Monsall Hospital:

“Dr Elizabeth Jones, Manchester’s medical officer for environmental health said a strong case could be made out for making AIDS a notifiable disease” — a status required if an application for detainment under section 38 of the Public Health (Control of Diseases) Act 1984 were to be pursued — which makes it plain she understood the legal constraint, an admission that forces the question of motive, because ignorance can be dismissed: was she driven by genuine public‑health precaution, political pressure, moral panic, or an intent to expand statutory power over marginalised groups, and as Roger’s solicitor and barrister outlined at the appeal, she submitted no coherent evidence other than an alleged letter from the consultant.

Dr Anna Jones acted with problematic motives although, with the above insight her understanding of the legal and ethical framework governing communicable diseases are open to scrutiny. What was proved was that her decision to pursue the order was the wrong one given the damage it threatened: in 1985, anyone testing positive for, or presenting with, AIDS — and later HIV — risked detention if another consultant like Jones made an unlawful application that was not scrutinised by a competent magistrate.

Roger’s case exposed how a single, inadequately informed or improperly motivated clinician could weaponise public-health powers, inflicting stigma, fear and potentially irreversible harm on vulnerable patients, and highlighted urgent deficiencies in oversight, legal safeguards and professional accountability.

It was alleged that Dr Jones appreciated the sensitivity and patient confidentiality surrounding AIDS in 1985 and that she requested the court hearing on her application be held in private (closed court), but the court rejected that request.

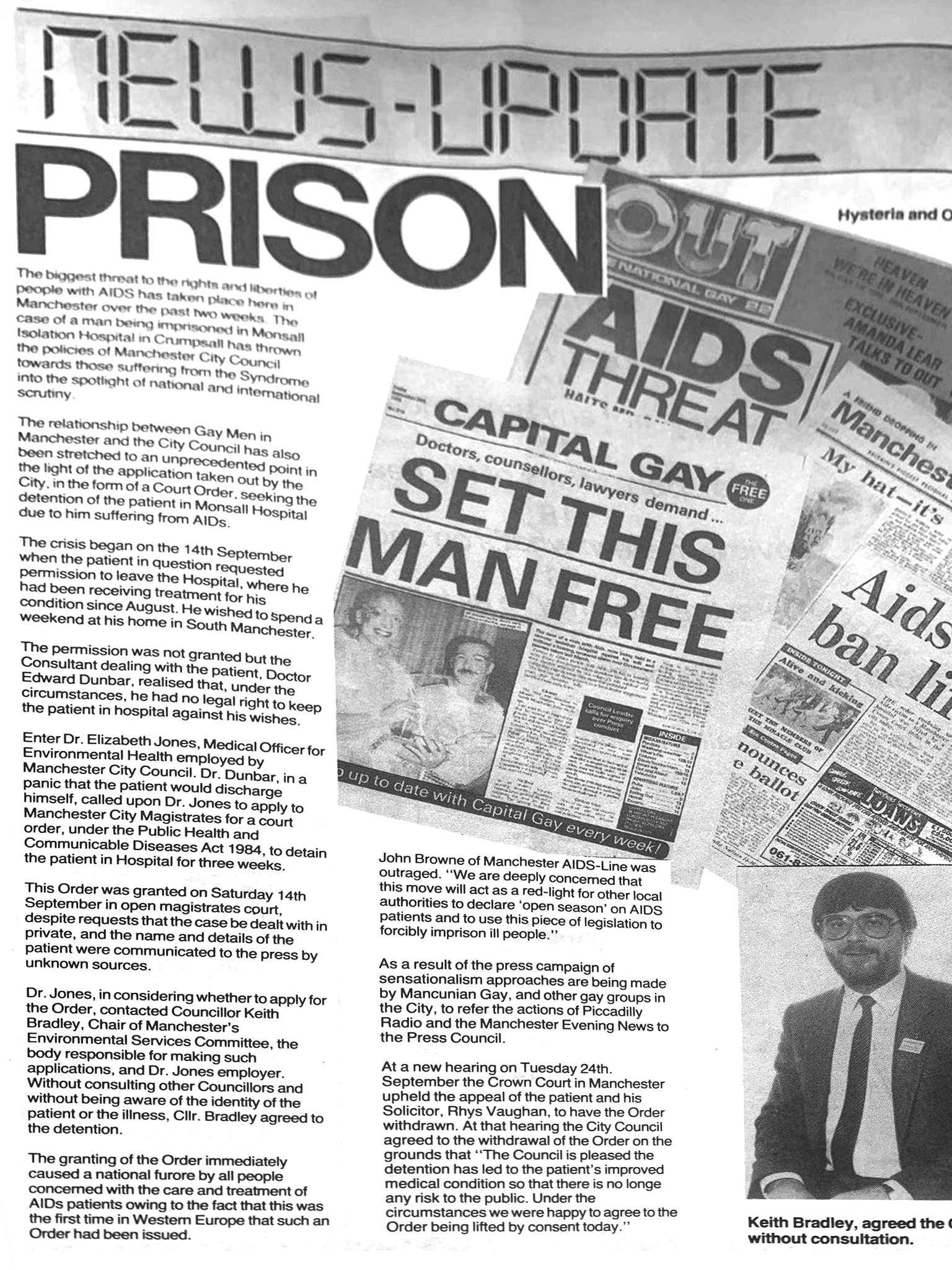

The ‘Mancunian Gay’ weekly newspaper reported in September 1985:

“Enter Dr. Elizabeth Jones, Medical Officer for Environmental Health employed by Manchester City Council. Dr Dunbar, in a panic that the patient would discharge himself, called upon Dr. Jones to apply to Manchester City Magistrates for a court order, under the Public Health and Communicable Diseases Act 1984, to detain the patient in Hospital for three weeks.

Dr. Jones, in considering whether to apply for the Order, contacted Councillor Keith Bradley, Chair of Manchester's Environmental Services Committee, the body responsible for making such applications, and Dr. Jones employer. Without consulting other councillors and without being aware of the identity of the patient or the illness, Cllr. Bradley agreed to the detention.

The granting of the order immediately caused a national furore by all people concerned with the care and treatment of AIDS patients owing to the fact that this was the first time in Western Europe that such an order had been issued”.

Three weeks after Roger won his appeal against his detainment, the Manchester Evening News reported on 16 October 1985 that the Labour council had “pledged” not to pursue similar orders against future AIDS patients, despite the fact that AIDS was not a notifiable disease and could not support such legal action.

The paper’s coverage highlighted a tense compromise: local authorities, under public and political pressure to protect community health, sought to reassure residents while critics warned the pledge masked a troubling readiness to use coercive measures against a vulnerable group. Medical professionals and civil liberties campaigners stressed that compulsory orders risked fuelling stigma and deterring people from seeking testing and care, and they urged clear public health guidance grounded in evidence rather than fear.

Interestingly, within the article they reported “The city’s now retired medical officer for Environmental Health, Dr Anna Jones…”.

“Now retired”? Coincidence — or perhaps a convenient euphemism for a forced exit, given the serious questions surrounding her conduct and the national furore over the unlawful detention of Roger Youd.

The claim Dr. Jones was “now retired” presented a departure without scrutiny, sanitising any accountability: Roger, the Youd family, supporters and readers deserved clear answers about whether her departure was voluntary or the consequence of professional failings, internal pressure or disciplinary measures following what many have called an act of ‘unlawful detention’.

Dr Anna Jones became an administrative medical officer in Manchester in 1962, rising through the ranks to deputy medical officer and, by 1985, to Manchester’s chief medical officer, where she oversaw major public health initiatives; her tenure later attracted controversy after she issued a detention order against a patient with AIDS that was deemed unlawful following a successful appeal by Roger’s barrister, and where she swiftly “retired” soon after the ruling.

Jones died on 17 August 2023.

Everybody I spoke with could only conclude that the order obtained against Roger was a panic decision rather than one grounded in reasoned malice; that view was echoed by the press, Roger’s solicitor and his barrister at the time of his appeal. I, like many others, perhaps feel the haste and deceitful manner in which the order was secured spoke of ‘panic’ — an urgent, ill-considered reaction — rather than a deliberate attempt to harm.

I have never been one to loosely connect the dots or speculate, however the contemporary coverage around two AIDS patients at Monsall Isolation Hospital between January and March 1985 perhaps helps explain why the consultant and the local authority might have panicked.

Both men, in their thirties, were publicly acknowledged by the hospital without being named, yet the Rochdale patient attracted disproportionate attention: the Rochdale Observer’s 30 January 1985 headline—“AIDS victim draws up contact-list”—framed him in a patient-zero narrative and emphasised his alleged wider travel, inviting intrusive inquiries and public alarm. In that febrile media climate, a local paper pushing an investigative angle would have amplified fears, pressured health officials for immediate action and disclosure, and made containment decisions appear urgent—even if, clinically, careful measured responses were more appropriate.

MONSALL HEADLINES: a handful of press from January-March 1985 concerning Monsall Hospital

One of the men (likely the Manchester man), like Roger, had expressed a wish to leave Monsall Hospital and go home only months (January 1985) before Roger’s own detainment (September 1985). A request the hospital acceded to given they later stated there had been an improvement in his health, and which was reported in the Manchester Evening News on 29 January 1985, a piece likely to unsettle readers and Mancunians anxious about a man with AIDS mingling with the general public.

Monsall Hospital 1985

Sadly, within days of his discharge the man rapidly deteriorated, was readmitted to Monsall Hospital and died, prompting the Manchester Guardian to run the stark headline “AIDS death — why victim went home”, noting at the top of its report that “the hospital authorities have defended their decision to allow the patient home for a few days.” The press probing the hospital exposed the fraught tension then between patient autonomy, institutional public relations and widespread fear and misinformation about AIDS, amplifying controversies about hospital policy, media responsibility and community anxieties in Manchester.

It was evident that media scrutiny had relentlessly pressed Monsall officials to ‘defend’ why they had permitted the man to go home, suggesting — with insinuations that an infectious AIDS sufferer might be circulating within the Manchester community — or perhaps that hospital negligence had contributed to his rapid deterioration and eventual death. That intense public and press pressure, and the fallout from the Hospital allowing the patient to ‘go home for a few days’, perhaps helps explain why only six months later Roger’s consultant and the chief medical officer, haunted by the consequences of the previous decision, reacted with alarm when Roger expressed a wish to merely return home.

In the absence of direct testimony from those who sought and obtained the order against Roger, leaves us with the most plausible explanation for the ‘panicked decision’ that precipitated their urgent steps to obtain a detainment order in Roger’s case as a defensive, risk‑averse response rooted in fear of repeating the intense and perhaps unfair scrutiny the hospital faced when it allowed the earlier patient (possibly the Manchester man), at his own request, to be discharged and allowed to go home. So when Roger too expressed a desire to go home, they reacted pre‑emptively to avoid a second wave of adverse attention, framing decisions more around perceived reputational risk than strictly medical or legal criteria.

On hearing the UK AIDS Memorial Quilt was accepting new panels, Roger was at the top of my list as I planned eight quilts for World AIDS Day 2025.

Quilts are usually made by those who knew a life intimately, but my knowledge of Roger Youd began only with the media coverage of his unlawful detainment in 1985, so I pieced together his Quilt from conversations with friends and family. I used a mirror ball motif to capture both his aspiration to be a DJ in Manchester and the idea of mirrors as reflections — fragments that reveal who he was beyond the media storm that surrounded his detainment — stitching those gleaned memories into a single, luminous quilt of remembrance.

His name gleams in red diamantes that catch the light and mirror his effervescent spirit, the ruby tone nodding to his Welsh roots while the twinkling stones suggest constant motion and joy. Beneath, where dates might usually be set, in gold the inscription reads “Lover of Vinyl Music,” stitched below the textured arm of a record player and a neat stack of vinyl records, beside gym gear and the shared pints of Guinness he enjoyed with his friend Ian.

The single ‘Saving all my Love’ by Whitney Houston lies within the design, quietly marking the date of his untimely passing at just 29; scattered across the mirrored panes of the disco ball, the Welsh Dragon as a nod to Roger’s birthplace. Lady Justice appears, scales balanced evenly with the word ‘Betrayal’ stretched across both plates, a stark reference to those who failed Roger and the family during his unlawful detainment; nearby, two clippings note his detention at Monsall Hospital and the subsequent appeal to which he won. An image of his Manchester home sits with equal weight — the modest terrace where he had rooted himself — alongside the ‘Reflections’ album cover by Evelyn Thomas, the Spin-Inn record shop façade and the familiar carrier bag from the shop that Roger no doubt used to carry his new purchases.

NEW QUILT: 2025

The insight in these panes is only available when you draw near, a deliberate intimacy that frames privacy as a permission—you must get up close to Roger’s quilt to get a brief insight into who he was. His name appears slightly smaller for the same reason, tucked modestly into the composition so that revelation requires proximity; from a distance it reads as a discreet signature, almost a whisper. From across the room, however, his quilt seizes the eye: a giant mirror ball scattered with hand stitched diamante fragments that catch and throw light, a sparkling shorthand for a life lived vividly. That distant flash announces him before the details are read, while the quiet typography and the need to approach invite a more careful, personal encounter, balancing spectacle with the tender work of discovery.

Given the entire Quilt measures 12ft x 12ft, Roger’s positioning within it is deliberate so when on display it can be observed at eye level.

Any third-party copyright material has been accessed through paid membership or incurred an administrative cost. Material has been used under the ‘fair use’ policy for the purpose of research, criticism and/or education, especially around the topic of HIV/AIDS. There has been no financial/commercial gain.